Which came first, religion or culture?

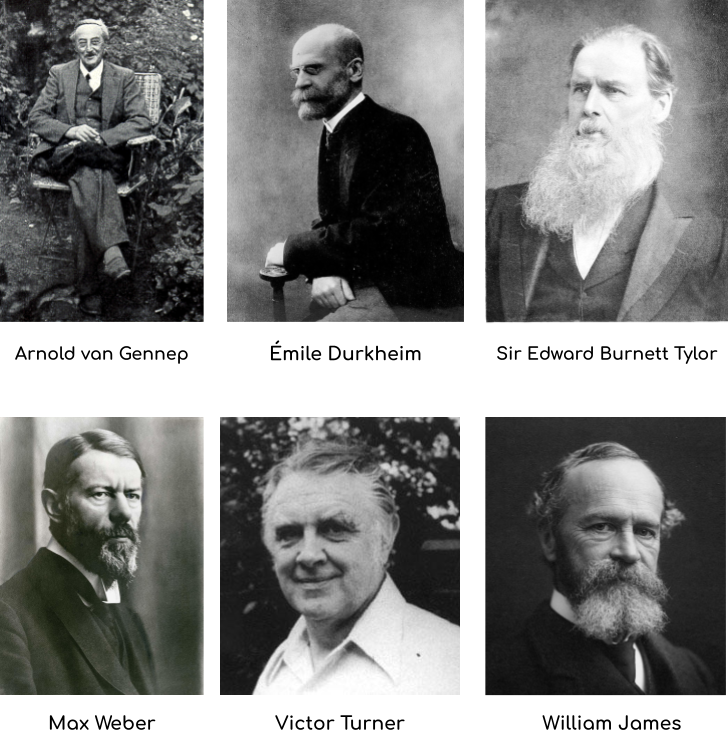

The relationship between culture and religion is more difficult in academic circles than in real life. For many years the study of religion, which took place in departments such as ‘Comparative Religion’, ‘Religious Studies’ etc. (which should not to be confused with Theology departments), used theories of late 19th and early 20th century scholars such as Edward Tylor, Émile Durkheim, Arnold van Gennep, Victor Turner, sometimes also Weber (whose emphasis was more sociological), William James (Religious Experience), and many others, all of whom (at least those I just mentioned) were serious scholars and deep thinkers. The work of most of these scholars was anthropological or tangential to it, and had its roots in the meeting of the Christian West with other cultures as a result of colonialism. It was, as far as they were concerned, unlike the political or economic advantage colonialism gained, an honest attempt to conceptualize local religion by comparing and contrasting, and in many cases also to establish explain the self-evident, for them, the superiority of Christianity. Nonetheless, their theoretic thinking was deep and serious, and they established concepts such as animism, totemism, Rites of Passage, liminality, which while not much used anymore, are the forerunner of the concepts current scholars are using in their academic work.

By the 80s and 90s, when I was at the beginning of my academic work on religion, and worked then on Ancient Christianity, these classical Comparative Religion theories did not supply what I needed for my analysis of the monastic text. The 90s were, however, a period when a great variety of cultural theories were at their peak, such as semiotics, postcolonialism, narratology, etc., and many more were soon to spread, such as the cognitive turn, network theory, optimization theory (in linguistics), and all the approaches that make use of the new digital technology. Looking into cultural theories in order to analyse religion was not very common then. Religion is a ‘total institution’, which is not looking outside to explain itself, and this was also the case with regard to theories that explain religions: people were looking for theories that would explain the phenomenon of ‘religion’, not thinking that ‘religion’ can be framed within another context. When looking into cultural theories, for explaining a certain behaviour, for example, I constantly felt the need to ask myself: is this now theorizing a religious phenomenon, or is it ‘only’ culture, and therefore falls outside the scope of my work, which is about ‘religion’?

Nowadays, in the first quarter of the 21st century, it is quite common to use cultural theories to explain religious phenomena. Many studies use narratology to analyse the biblical text, or semiotic concepts to look into phenomena that are classified as part of ‘religion’, for example, ritual.

However, this is not a two way traffic; scholars of cultural studies tend to ignore religion, by working around it, or ignoring the category altogether; they also ignore the theories that were developed to study religions. I suspect that this happens because theoreticians of culture come from secular circles of the society, who look at religion, as well as theories of religion, as the thing of the past. Indeed, the sociological, anthropological theories of the 19 and beginning of the 20th century, take a colonialistic perspective or are busy validating Christian type of religions, and thus usually not accepted nowadays. But these theories were sensitive to things that cultural theories are less aware of, for example the diverse forms of binding factors in a society, the strength of group solidarity, the acceptance of a hierarchical social system, all of which go against current secular Western stated ideologies of equal opportunity and self expression. Without going into the discussion whether these ideologies are actually realized, the colonial concepts referred to above still help explain social realities.

This is not a historical overview of the relationship between the study of culture and religion, it is only my own experience, which led me to formulate the relationship between the two phenomena by developing the concept of Sealing the Semiosphere.

The word ‘seal’ here means ‘a stamp of approval’, and the word ‘semiosphere’ refers to the ‘cultural reality’. Explaining ‘religion’ as ‘sealing the semiosphere’ is explaining religion as a cultural phenomenon, regardless of what the content of it is. Sealing the Semiosphere points to a certain cultural process, and religion is one example of this process.

The best way to explain this process is to think of the meeting point between Gofman’s concept of ‘total institution’ and Handleman and Lindquist’s concept of ‘holism’. Gofman defines a total institution as “a place of residence and works where a large number of like-situated individuals cut off from the wider society for an appreciable period of time together lead an enclosed formally administered round of life” (p. 11). I take from this the idea that an institution (and for my purpose, not only a place of residence or work) has the authority to create the cultural reality for its members, creating, in fact, their reality in its entirety.

In the introduction to their volume of articles, Handelman and Lindquist are saying that “human propensity toward holistic organization is in multiple domains, on multiple levels, is profound and cannot be reduced simplistically to historical processes nor to particular social formation” (p. 20). What they explain is that humans feel the need to integrate all their reality into a unified explanation, that is, not only to explain every single thing that they encounter, but to explain the entirety as one system.

The combination of being total, according to Gofman’s definition, and explaining the entirety, as in Handelman and Lindquist, results in a social institution that has the authority of creating and maintaining reality.

This is what religion does.

Looking at religion from this perspective, frames it as a cultural phenomenon. However, the details about the content and nature of what we now call ‘religion’ is a topic for a separate post.

Sources for the photos:

Arnold van Gennep: https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arnold_van_Gennep#/media/Bestand:Van_gennep2.gif

Emil Durkheim: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89mile_Durkheim#/media/File:%C3%89mile_Durkheim.jpg

Edward Burnett: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/28/E._B._Tylor_portrait._Folk-Lore%2C_vol._28.png

Victor Turner: https://www.nndb.com/people/333/000099036/

Max Weber: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Max_Weber#/media/File:Max_Weber,_1918.jpg

William James: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_James#/media/File:William_James_b1842c.jpg